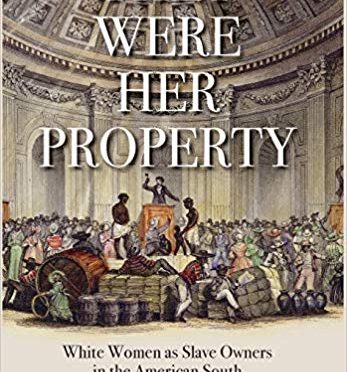

Historian Stephanie Jones-Rogers discusses her new book about the role of white women in American slavery. They Were Her Property reveals that slave-owning women were sophisticated economic actors who directly engaged in and benefited from the South’s slave market.

RECORDED April 17, 2019

In They Were Her Property, Jones-Roger writes that women typically inherited more slaves than land, and that enslaved people were often their primary source of wealth. Not only did white women often refuse to cede ownership of their slaves to their husbands, they employed management techniques that were as effective and brutal as those used by slave-owning men. White women actively participated in the slave market, profited from it, and used it for economic and social empowerment. By examining the economically entangled lives of enslaved people and slave-owning women, Jones-Rogers presents a narrative that forces us to rethink the economics and social conventions of slaveholding America.

Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers is assistant professor of history at the University of California, Berkeley.

How does slavery in New England and women’s role in the slave system there compare to Stephanie Jones-Rogers’ findings?

Margaret Ellen Newell

Professor of History at Ohio State University and author of Brethren by Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery

Stephanie Jones-Rogers paints a devastating portrait of white women’s role in constructing and perpetuating the evils of slavery in the antebellum South. My work focuses on an earlier period, and on slavery in the North, so there are some differences.

One is that most enslaved people in New England before 1700 were Native Americans captured in warfare, kidnapped, or forced into servitude by colonial courts. After 1720 New England merchants made enslaved Africans more available to local markets and their numbers grew.

Another difference is that most enslaved people did not work on plantations or live in separate slave quarters. Families and households were the core economic unit where most goods were produced and consumed. Outside of the Narragansett area of Rhode Island and a few other exceptionally large slaveholders, like the Royall family in Medford, few white New Englanders owned more than one or two slaves.

This meant that enslaved people lived in the small homes of their white masters and mistresses, sleeping on floors in bedrooms and kitchens, eating at the same table, always in close proximity. This should be our mental picture of life in colonial New England. Slaves worked alongside their white owners, doing the same jobs. Enslaved women took care of children and did the many tasks it took to keep a colonial household fed and clothed: cooking, baking, spinning, weaving, doctoring, dairying, and sometimes agricultural work. Enslaved men farmed, worked as skilled laborers and as sailors, whalers, fishermen and soldiers. Children tended livestock.

Some of the other patterns Professor Jones-Rogers identifies do apply to New England, especially her point that slavery was about capitalism. New Englanders wanted the labor of enslaved Indians and Africans. As in the antebellum South, New England parents tended to leave real estate to boys and movable property–including enslaved people–to girls. Widows and women with power of attorney, like Mercy Raymond of Fisher’s Island, bought and sold involuntary servants as if they were commodities, or leased out enslaved workers as a form of income. Susannah Winslow had Governor John Winthrop help her sell an Indian man named Hope to Barbados in 1648.

White women in New England were major beneficiaries of the labor of enslaved women. They likely attended auctions of war captives in New London and Boston Common, or requested that their husbands acquire slaves, like the minister Peter Thacher, who purchased an African slave and an Indian slave when his wife was pregnant with their second child. Colonial patriarchy gave ultimate authority to husbands, but white women wielded significant power over children, servants, and slaves in the household, including the task of physical punishment and supervision of labor.

And, there is evidence that women liked being slaveholders. Judge and diarist Samuel Sewall recorded requests from female acquaintances for Indian boys to drive their carriages, and most people in his Boston circle owned slaves. A widow that Sewall courted, Madam Winthrop, broke off their relationship over concerns that Sewall might make her free her Indian slave, Juno.

A few other potential differences are worth noting. The management of slave childbearing for profit that Professor Jones-Rogers describes seem not to have been common in colonial New England. This may be because New England’s law of slavery–the first in the English colonies–did not state that slavery was an inheritable status shared by children of the enslaved.

Another important point is that a wife’s role in New England was to teach and catechize all children in the household, including servants and slaves. This created emotionally complex relationships between enslavers and the enslaved. Joseph Quasson, a Monomoy Indian sold into servitude to pay his family’s debts, recalled that his mistress, Mary Sturgis, taught him to read and write. She was, he remembered, “like a mother to me.” She also terrified him with tales of hellfire and “corrected” him–with a whip. Joseph lost all contact with his own family and culture, including his ability to speak Wampanoag. So, there existed what historians call “affective bonds” in these New England slaveowning households, but they came at a terrible cost to the enslaved victims and did not mitigate the harsh realities of slavery.