Back in 1980, Cambridge Forum presented a series of radio and tv programs inspired by the 19th century preacher abolitionist, and humanitarian William Ellery Channing (1818-1901).

Channing was a transcendentalist poet who sought to bring a more humane spirit to bear on the conduct of life itself. He was known for his articulate and impassioned speeches that helped shape liberal theology of the day. The CF series, I call that mind free featured important speakers addressing the moral issues at stake in controversies of the era. The name for the series came from a famous Channing quote:

I call that mind free, which jealously guards its intellectual rights and powers, which calls no man master, which does not content itself with a passive or hereditary faith, which opens itself to light whencesoever it may come.

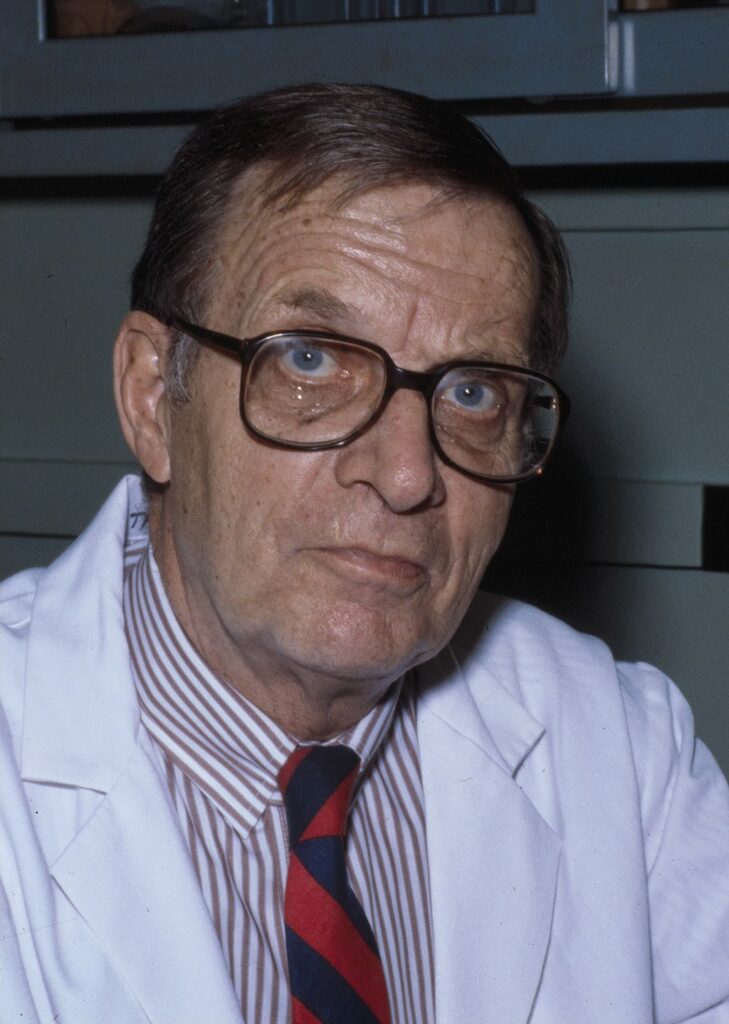

One program featured the late Lewis Thomas, president of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Dr. Thomas’ two books, The Lives Of A Cell and, The Medusa and the Snail, as well as his endeavors in science helped bridge the gap between the humanities and the sciences. His sense of wonder, his touch of the poet, and ability to put familiar things together in entirely new ways put him in the vanguard of social thinkers and humanitarians that William Ellery Channing exemplified.

The late Lewis Thomas, M.D. served as chancellor of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in Manhattan.

He contributed essays to the New England Journal of Medicine. One collection of those essays is The Lives of a Cell: Notes of a Biology Watcher (1974), also The Medusa and the Snail and Late Night Thoughts on Listening to Mahler’s Ninth Symphony.

In 1980, Dr.LewisThomas was the Phi Beta Kappa orator at the Harvard College commencement in Cambridge, MA.

“I believe that puzzlement. is an identifying characteristic of the human species.

Genetically governed. universal and a central determinant of human behavior. I can go this far with sociobiology, but then, influenced by this same human trait, my mind falls away in confusion. Uncertainty. The sure sense that the ground is shifting at every step is one of the marks of humanity. We keep changing our minds together in a biological process rather similar in its outlines to evolution itself.

The great body of science, built like a vast hill over the past 300 years, is a mobile, unsteady structure made up of solid enough single bits of information, but with all the bits always moving about, fitting together in different ways, adding new bits to themselves with flourishes of adornment as though consulting a mirror and giving the whole arrangement something like the unpredictability and unreliability of living flesh. Human knowledge doesn’t stay put. It evolves by what we call trial and error, or as is more usually the sequence, error and trial. Other animals differ from us in this respect. Each of them has at least one thing to be very good at, even superlatively skilled, sure footed. Any beetle can live a flawless, impeccable life.infallible at the business of procreating beetles. Not us.

We are not necessarily good at anything in particular except language. and using this we tend to get things wrong. It is built into our genes to veer off from the point. Somehow or other. we have been selected in evolution for the gift of ambiguity, and this is how we fell into the way of science. The endeavor is not, as is sometimes thought, a way of building a solid, indestructible body of immutable truth with fact laid precisely upon fact in the manner of twigs in an anthill. Science is not like this at all. It keeps changing, shifting, revising, discovering that it was wrong, and then heaving itself explosively apart to redesign everything. It is a living thing, a celebration of human fallibility, and at its very best it is rather like an embryo.

Ordinarily, scientists do not talk this way about their trade because there is always in the air the feeling that this time we have it right. This time we are about to come into possession of a finished science, knowing almost everything about everything. Biology has been moving so fast in just the last few years that there is some risk of making it seem nearly complete at the very stage in its development when it is in real life just getting ready to take off. It is nothing like finished. It is only just at its beginning. We are in trouble whenever persuaded that we know everything.

Today, an intellectually fashionable view of man’s place in nature is that there is really no great problem. The plain answer is that it makes no sense, no sense at all. The universe is meaningless for human beings. We bumbled our way into the place by a series of random and senseless biological accidents. The sky is not blue. This is an optical illusion. The sky is black. You can walk on the moon if you feel like it. But there is nothing to do there except look at the Earth. And when you’ve seen one Earth, you’ve seen them all.

The animals and plants of the planet are at hostile odds with one another, each bent on elbowing any nearby neighbor off the Earth. And genes. tapes of polymer are the ultimate adversaries, and by random, the only real survivors.

This grasp of things is sometimes presented as though based on science, with the implication that we already know most of the important knowable matters. And this is the way it all turns out. It is the wisdom of the 20th century, contemplating as its only epiphany the news that the world is an absurd apparatus and we are stuck with it and in it. And in the circumstance we would surely have no obligations except to our individual selves and of course, to the genes coding out those selves. I believe something considerably less than this. I take it as an article of faith that we humans are a profoundly immature species, only now beginning the process of learning how to learn.

Our most spectacular biological attribute, which identifies us as our particular sort of animal, is language. And the deep nature of this gift is a mystery. We are aware of our consciousness, but we cannot even make good guesses as to how this awareness arises in our brains, or even, for that matter, that it does arise there for sure. We do not understand how a solitary cell fused from two can differentiate into an embryo, and then into the systems of tissues and organs that become us. Nor do we know how a tadpole accomplishes his emergence, nor even a flea. We can make up instant myths, transiently satisfying, but always subject to abandonment about the origin of life on the planet.

We do not understand why we make music or dance or paint or write poems. We are bewildered, especially in this century, by the pervasive latency of love. The thing about us that should astonish biologists more than it does is that we are so juvenile a species. By evolutionary standards of time, we only just arrived on the scene, fumbling with our new thumbs, struggling to find our legs under the weight and power of our new brains. We are the newest and most immature of all significant animals. Maybe a million or so years along as the taxonomists would define us, but probably only some thousands of years as communal speaking creatures uniquely capable of manufacturing metaphors and therefore recognizable as human.

Our place in the life of the world is still unfathomable because we have so much to learn, but it is surely not absurd. We matter. For a time anyway, it looks as though we will be responsible for the thinking of the system, which seems to mean at this stage a responsibility not to do damage to the rest of life if we can help it. This is itself an immensely complicated problem in view of our growing numbers and the demands we feel compelled to make on the planet’s resources. There is no hope of thinking our way through the quandary except by learning more. And part of the learning, not all of it, mind you, but part, can only be achieved by science. More and better science. Not for our longevity or our comfort or affluence, but for comprehension, without which our long survival is unlikely.

The culmination of a liberal arts education ought to include, among other matters, the news that we do not understand a flea, much less the making of a thought. We can get there someday if we keep at it, but we are nowhere near, and there are mountains and centuries of work still to be done.

One major question needing to be examined is the general attitude of nature. A century ago, there was a consensus about this. Nature was red in tooth and claw. Evolution was a record of open warfare among competing species. The fittest were the strongest aggressors, and so forth, and now it begins to look different. The tiniest and most fragile of organisms dominate the life of the Earth. The chloroplasts inside the cells of plants, which turn solar energy into food and supply the oxygen for breathing appear to be the descendants of ancient blue green algae, now living as permanent lodgers within the cells of what we like to call higher forms, and the mitochondria of all nucleated cells, which serve as engines for all the functions of life, are the progeny of bacteria which took to living as cells inside cells long ago.

The urge to form partnerships to link up in collaborative arrangements is perhaps the oldest, strongest and most fundamental force in nature. There are no solitary, free living creatures. Every form of life is dependent on other forms. The great successes in evolution, the mutants who have, so to speak, made it, have done so by fitting in with and sustaining the rest of life. Up to now, we might be counted among the brilliant successes, but flashy and perhaps unstable. We should go warily into the future looking for ways to be more useful, listening more carefully for the signals, watching our step, and having an eye out for partners.

The greatest single achievement of nature to date was surely the invention of the molecule of DNA. We have had it from the very beginning. Built into the first cell to emerge, membranes and all, somewhere in the soupy water of the cooling planet, 3000 million years or so ago. All of today’s DNA strung through all the cells of the Earth is simply an extension and elaboration of that first molecule. In a fundamental sense, then we cannot claim to have made progress, since the method used for growth and replication is essentially unchanged. It is a lucky thing for us that nature has exhibited such restraint and good taste in evolution. Given brains of the size and complexity of ours, capable of manufacturing an infinity of sentences in strings long enough to stretch from here to the sun and back again, we are given, at the same time, a sense of limitation preventing us from settling all our affairs once and for all, by words alone. In a lesser world, we might have been condemned long ago to string out one huge set of sentences, wrapping ourselves in a cocoon of changeless words, immutable, in which to live forever, like the termites who can never revolutionize the inner structure of their hills. We, in contrast, can make up new thoughts whenever we feel like it. Nature has been kind to us, leaving us leeway, never piling it on too much. Having been given brains with a certain power but limited by a certain fallibility, we are better equipped for finding our way through the future.

Our minds are like our hands. It was a marvelous thing to come down from the trees with an opposing thumb, the language maker of the hand. But that was good enough for our needs, and we can be eternally grateful not to have, as we might have had, brains that are all thumbs. But maybe, given the fundamental instability of the molecule, it had to turn out this way. After all, if you have a mechanism designed to keep changing the ways of living, and if all the new forms have to fit together as they plainly do on this planet, with symbiotic living all over the place, and if every improvised new gene representing an embellishment in an individual is a candidate for selection for the species, if it turns out to be useful for others. And if you have enough time, maybe the system is simply bound to develop brains sooner or later. And awareness.

Biology needs a better word than error for the driving force in evolution. Or maybe error will do after all, if you remember that it came from an old Indo-European root meaning to wander about looking for something. I cannot make my peace with the randomness doctrine. I cannot abide the notion of purposelessness and blind chance in nature, and yet I do not know what to put in its place for the quietening of my mind. It is absurd to say that a place like this place is absurd when it contains in front of our eyes so many billions of different forms of life, each one in its way, absolutely perfect, all linked together to form what would surely seem to an outsider, a huge spherical organism.

We talk, some of us anyway, about the absurdity of the human situation. But we do this because we do not know how we fit in or what we are for. The stories we used to make up for to explain ourselves to ourselves do not make sense anymore, and we have run out of new stories for the moment. Some people believe that we are in trouble because of science, and that we should stop doing science and go back to living in nature with nature, contemplating nature. It is too late for us to do this. Too late by several hundred years, and there are now too many of us here. 4 billion already, with the likelihood of doubling that population and doubling it again within the lifetime of some of the people here.

What I would like to know most about the developing Earth is does it have a mind? Or will it someday gain a mind? And are we part of that? Are we a tissue for the Earth’s awareness? I like this thought, even though I cannot take it anywhere, and I must say it embarrasses me. I have that nagging hunch that it is a presumption, a piece of ultimate hubris. A single insect may have only two thoughts, maybe three, but there are a lot of insects. The million blind and almost mindless termites in the hill make up in their collective life and intelligence, a kind of brain now capable of building endless vaulted chambers and turning perfect arches, thinking all the way. I would like to know what whales are thinking about, orr dolphins, but if I were hoping to find out how intercommunication really works on this planet, I would study termites.

I am willing to predict uncertainly, provisionally, that there is, after all, one central universal aspect of human behavior genetically set by our very nature, biologically governed, driving each of us along. Depending on how one looks at it, it can be defined as the urge to be useful. This urge drives society along, sets our behavior as individuals and in groups, and invents all our myths, writes our poetry, composes our music. This is why it is so hard being a juvenile species, still milling around in groups, trying to construct a civilization that will last. Being useful is easy for an ant. You just wait for the right chemical signal at the right stage of the construction of the hill, and then you go looking for a twig of exactly the right size for that stage, and carry it back up the flank of the hill and put it in place. And then you go and do that thing again. An ant can dine out on his usefulness all his life and never get it wrong. It is a different problem for us carrying such risks of doing it wrong, getting the wrong twig, losing the hill, not even recognizing yet the outline of the hill. We are beset by strings of DNA, immense arrays of genes instructing each of us to be helpful, impelling us to try our whole lives to be useful, but never telling us how. The instructions are not coded out in anything like an operator’s manual. We have to make guesses all the time. The difficulty is increased when groups of us set to work together. I have seen and sat on numberless feckless committees, not one of which intended anything other than great merit. Larger collections of us, cities for instance, hardly ever get anything right, and of course, there is the modern nation, probably the most stupefying example of biological error since the age of the great reptiles. Wrong at every turn, but always felicitating itself loudly on its great value. It is a biological problem, as much so as a coral reef or a rainforest, but such things as happened to human nations, error piled on error could never happen in a school of fish. It is, when you think about it, a humiliation. But then humble and human are cognate words, both derived from an old root meaning simply Earth. We are smarter than the fish, but their instructions come along in their eggs. Ours we are obliged to figure out, and we are in this respect, slow learners and error prone.

If you are going to make up a story about the Earth based on today’s scientific information, it is useful to have a third person to tell the tale. And for this role, I summon that sagacious and ubiquitous gentleman known as the extraterrestrial visitor. Zipping through our part of the galaxy, his attention is caught by our small suburban solar system, and he comes in among the planets, carrying along a number of instruments in a vehicle whose details I need not bother imagining. He spots the earth and sees the difference, immediately moving in for a closer look. No matter where he came from or what he has seen before, I take it for granted that his first reaction is an indrawn breath at its sheer beauty. I have no doubt that there are colonies of life elsewhere in the universe, and perhaps he has seen them all. But I choose to doubt that there can be many celestial bodies at the very springtime of their development, marked so extravagantly by exuberance, youth, and perfection of detail as this one. Let me change the story here to insert more time. He sees the Earth now, but he is one of the older extraterrestrial visitors and has been making periodic detours in our direction since the birth of the structure. The laying down a bone for a billion or so years ago and taking time lapse photographs close up every few hundred thousand years. Running the whole film through this year, say, what sort of impression would he have of us? I think he would conclude that his lens had caught the gestation still in progress, of a stupendous embryo, clinging to a warm, round stone by what we call Earth, or soil, as though attached all around by a kind of placenta, and turning slowly in the sun. He would have seen this creature starting from a single cell, fertilized by lightning, or ultraviolet light, or cosmic rays, or what have you. For 2 billion odd years, he would observe the formation of a sort of blastula, a huge cluster of cells multiplying first in the sea and later on land, all pretty much the same kind of primitive non-nucleated cell. Then the film would show a green tinge here and there, and then with the appearance of oxygen and thanks to the sun, an explosive emergence of new forms of life would be seen everywhere. New cells with nuclei, new collections of cells gathering to form tissues, coral reefs, and finally roses and dolphins, and then at last, ourselves off and running, making metaphors and music the newest and youngest working parts of the planet. I would like to think that we are on our way to becoming an embryonic central nervous system for the whole system. I even like the notion that our cities, still primitive, archaic, fragile structures, could turn into the precursors of ganglia to be ultimately linked in a network around the planet. But I do worry from time to time about that other possibility, that we are a transient tissue replaceable, biologically representing a try at something needing better means of perfection, and therefore on our way down under the hill, interesting fossils for contemplation by some other kind of creature. In my more depressed moments, I find this a plausible form of heart sink.

But at better times, remembering how skilled our species is with language and metaphor almost from birth, how good we are at recognizing and recording our mistakes, and how spectacularly we excel all other creatures on this planet, because of the emergence of Johann Sebastian Bach as an example of what we can do as a species, when we really try to use our brains, and remembering that nature is by nature parsimonious, tending to hang on to useful things when they really do work, I have hopes for our survival into maturity millennia ahead. Perhaps after all, we do have a long way to go. And if this is so, we have a lot to learn. and I do like that thought. It is, after all, the oldest of human ideas and still the best of all. Thank you. “